Quelle courage! Everson didn’t fear anyone in the film history or crit game when he first penned and published his thorough take on the American silent film era in his 1978 book. He dissed other writers, historians, critics, scholars, and even Frank Capra. He also doesn’t hold back on sprinkling in his political beliefs either. But, if you can see past all that, you’re in for a good history lesson on the early days of American cinema and beyond. Sort of like having that professor everyone hates but must admit: he is the best.

|

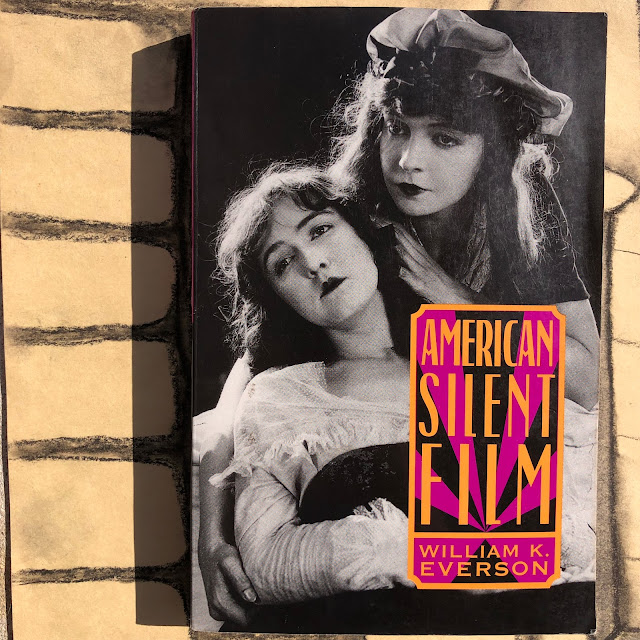

| Photo by Chris Mich. Background artwork by Lily Mich. |

Everson gives the reader a lay of the silent film land and wastes little time before establishing the importance of David Wark Griffith. Yes, the reader is forced to endure pages upon pages on The Birth of a Nation (1915) – as well as additional D.W. Griffith titles including Judith of Bethulia (1914) and Intolerance (1916). That’s because, despite all the controversy around his work, Griffith built the language of film in shot selection, editing, and more. But this is basic Film 101 stuff.

When Everson pulls back the curtain on the film industry, explaining the loosey-goosey distribution tactics in a business in its infancy, he paints a wild west portrait of silent film with major city Film Exchange offices sporting gaudy-yet-colorful film posters to the first batch of 500-seat theatres charging $.08 admission. Motion pictures rule the teen years of the 20th century as the ONLY mass entertainment business and, due to its evolution out of vaudeville, was unable to quickly secure a respectable “art” status. Until sound, color, superior effects, and all that the film industry would ultimately have at its creative disposal, it had to be both ART and COMMERCE and define its method in both areas on the fly.

Silent film writers, directors, stars, and critics of the teen years are discussed before Everson leaps into the glory days of the 1920s and [exhausted sigh] visits Griffith once more.

The real payoff is when Everson tackles genres within the silent era midway through the book. How I wish I read this when I was researching my last published article on The Blob (1958) – which, I’m sure, Everson would have HATED. His words on academic film writing: “This kind of super-intellectualization of film is in some ways even more dangerous than mediocrity because it is dull, deadening interest instead of stimulating it” (355). Everson preached this…in his nearly 400-page analysis of the silent era. Pot meet kettle. At any rate, Everson’s breakdown of genres was insightful.

Genres, according to Everson, include: Satiric Comedy, Sight-Gag Comedy, The Love Story, Animated Cartoons, Spectacle, The Detective Story, The Horror Films, The Western and Gangster Films (note that this is one category involving both cowboys and modern criminals), and The Documentary. Everson does an excellent job including stars and titles per genre, explaining how the genre formed in the silent era and then transitioned with the invention of talkies. His most interesting take was how animators waited until the silent comedy film stars Chaplin, Lloyd, Keaton, Larry Semon, Laurel and Hardy, and others phased out. Animators went on experimenting and perfecting the craft and then, once sound killed the silent stars, took over the family comedy scene. But Everson said the nails were driven into the coffin FOR ANIMATION in the 1950s – when quality cartoons became too costly to make and efficiency took over the industry. Everson commented, “The decline of the cartoon from that point on was rapid and tragic.” Interesting. I guess animation innovators like John Lassater, Hajime Yatate, Glen Keane, John Pomeroy, Matt Groening, Genndy Tartakovsky, Lenora Hume, Rebecca Sugar, Nick Park, Hayao Miyazaki, Steven “Spaz” Williams, Carl Macek, Katsuhiro Otomo, and Phil Tippett didn’t get that memo since they went on to lift animation to new levels of greatness post-1950.

Everson ends his book with a diatribe on what film history sources you should consider reading but spends even more ink on what he thinks you should NOT read. He pulls no punches.

While a lot of Everson's writing raised my eyebrow in disbelief or disappointment, he won me over with his take on my favorite Buster Keaton film, One Week (1920). “…Possibly the single funniest film of [1920],” he wrote, “and by any standards was one of Keaton’s best” (156). I’ll go one step further, William K. Everson: One Week was Keaton’s best.

Film enthusiasts are an opinionated bunch. But, if they know their stuff, I’ll listen…or read. And, with that in mind, American Silent Film is worth the read.

Special thanks to Out of the Past blogger Raquel Stecher for hosting the 2023 Classic Film Reading Challenge. This post is an official entry. To join us in this fun summer endeavor, visit

her blog for more details.

#classicfilmreading

Thanks for this! Eeeh I'm not sure I can get passed everything you pointed out about the author. That would be too off-putting for me.

ReplyDeleteI found myself going, "Hmph. Really?!" a lot while reading this. But the author is extremely knowledgeable and does an excellent job organizing an entertaining historical walk through the early days of cinema. But definitely not a cup of tea for just any ol' reader.

Delete